Remembering visual and sound artist Steve Roden, 1964-2023

A singular artist with a singular aesthetic, his collections helped fuel his muse.

easy - to know

that diamonds - are precious

good - to learn

that rubies - have depth

but more - to know

that pebbles - are miraculous

— Josef Albers

Brilliant. A must have for anyone interested in life.

— Ping Buzzer 1

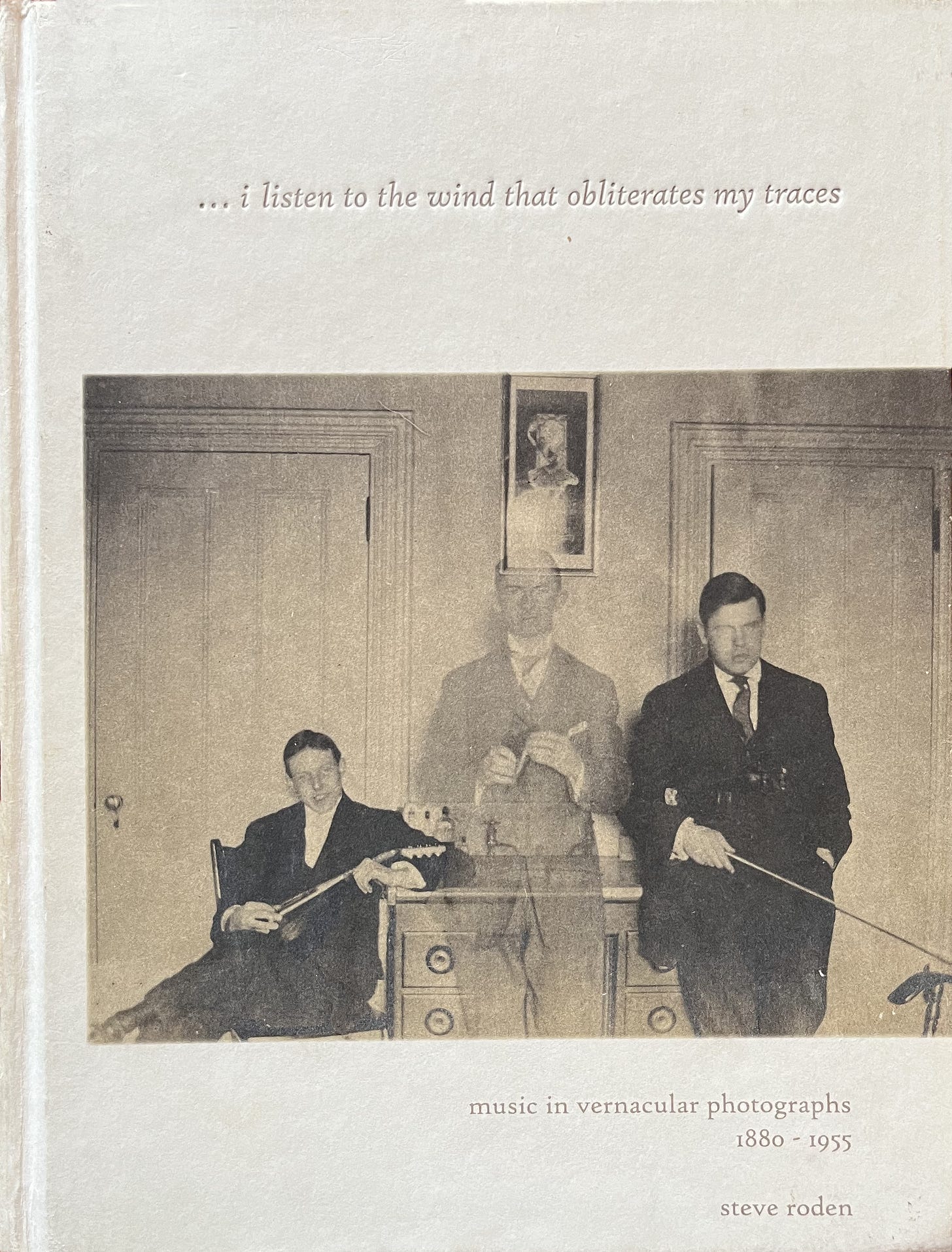

The top epigraph is one that Steve Roden quoted in one of his creations. The second one is from an Amazon review of … i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces …, Steve’s 2011 book and double CD collection of found photos and sound.

Steve died on Wednesday after living with early onset Alzheimer’s for six years, a particularly cruel curse on someone whose mind was constantly, gleefully absorbing objects, artifacts and ideas and transforming them into uniquely Rodenesque works. His passing has prompted an outpouring of grief in the LA art and sound community and among the hundreds of students he taught over the years. He was not just interested in life. He was obsessed with the remnants of it, the so-called detritus. The traces.

I understood the depths of his obsessions when, one night during a regular series of listening sessions that me and Eothan Alapatt hosted in the mid-’10s, Steve described his hours-long quests for strange, obscure, screaming-from-your-speakers-weird records. A night-person, he spent his late hours scouring eBay for 45s, found photos, odd artifacts and otherwise seemingly impossible items. Pre-Discogs, he described his search methods and discovery strategies.

Steve wasn’t part of the vinyl collecting community, per se. He collected alone and not to sell; he collected because that’s what he did, and the stuff he brought to the sessions was utterly alien. The group included some serious heads — Egon, Taylor Rowley, Zach Cowie, Gaslamp Killer, Brian Shimkovitz (Awesome Tapes from Africa), Toddrick Spalding (Sonic Ritual), Patrick McCarthy (Temporal Drift) and Jon Ward (Excavated Shellac) all attended at one point or another — and most sessions at the end of the evening we’d leave slack-jawed over what Steve had brought. I wish I’d recorded at least one 45 that played, or kept better track of those sessions.

His own music was mostly beatless, and focused on hiss, found sound, distance, naturally-occurring rhythms. It wasn’t stuff you could tap your foot to, residing instead in the space between the taps, when your sole’s on a collision course with the ground but not yet halted.

We’d first met in 2009 when I was part of a USC-Annenberg arts journalism fellowship. A group of us visited Steve and his wife Sari at the Bubble House, where they lived. Built by architect Wallace Neff, the striking Pasadena house is … well, see for yourself:

It was built by inflating a giant balloon. He enjoyed living there, he told me, but it was also kind of an albatross. Steve described it as “a little like being the caretaker of someone’s project” in a 2004 story for the LA Times.

That many of his own projects were born within someone else’s is fitting; Steve thrived when coming upon something wondrous and breathing new life into it. He turned the house’s non-bubble garage into his studio, generating paintings, sculptures, sound pieces and multimedia explorations with the devotion of someone obsessed and beguiled with this wondrously fucked-up world.

I got to write about Steve in 2011 when I was pop music critic at the Times. Though hardly pop music, he’d teamed with the archival label Dust-to-Digital to release … i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces …. We spoke for hours about the work, the quest, the collecting and the meaning. I’m republishing it here.

Steve Roden: ‘This is how it always happens — I found a photo’

Originally published in the Los Angeles Times on July 31, 2011.

The genesis of “... i listen to the wind that obliterates my traces,” a new book of vintage photographs with musical accompaniment, came simply, during one of artist Steve Roden’s regular visits to the flea market.

“This is how it always happens — I found a photo,” says Roden with a tone of amused resignation, relaxing on a couch in his Pasadena living room. The photo, he recalls, was of two guys sitting on a lawn; one was playing a clarinet, and the other had a mandolin. Standing between them was a howling coyote, which appeared to be singing along.

“I just stared at this photo for ages,” he recalls. “I was like, this is so amazing. I should try and make a piece of music based on this image, because it’s so strange.” Though best known for his visual art, Roden makes sound sculptures and conducts sonic experiments, and this seemed at first like a perfect springboard. “And then I realized, I don’t need to make music from this image — because it doesn’t need me.”

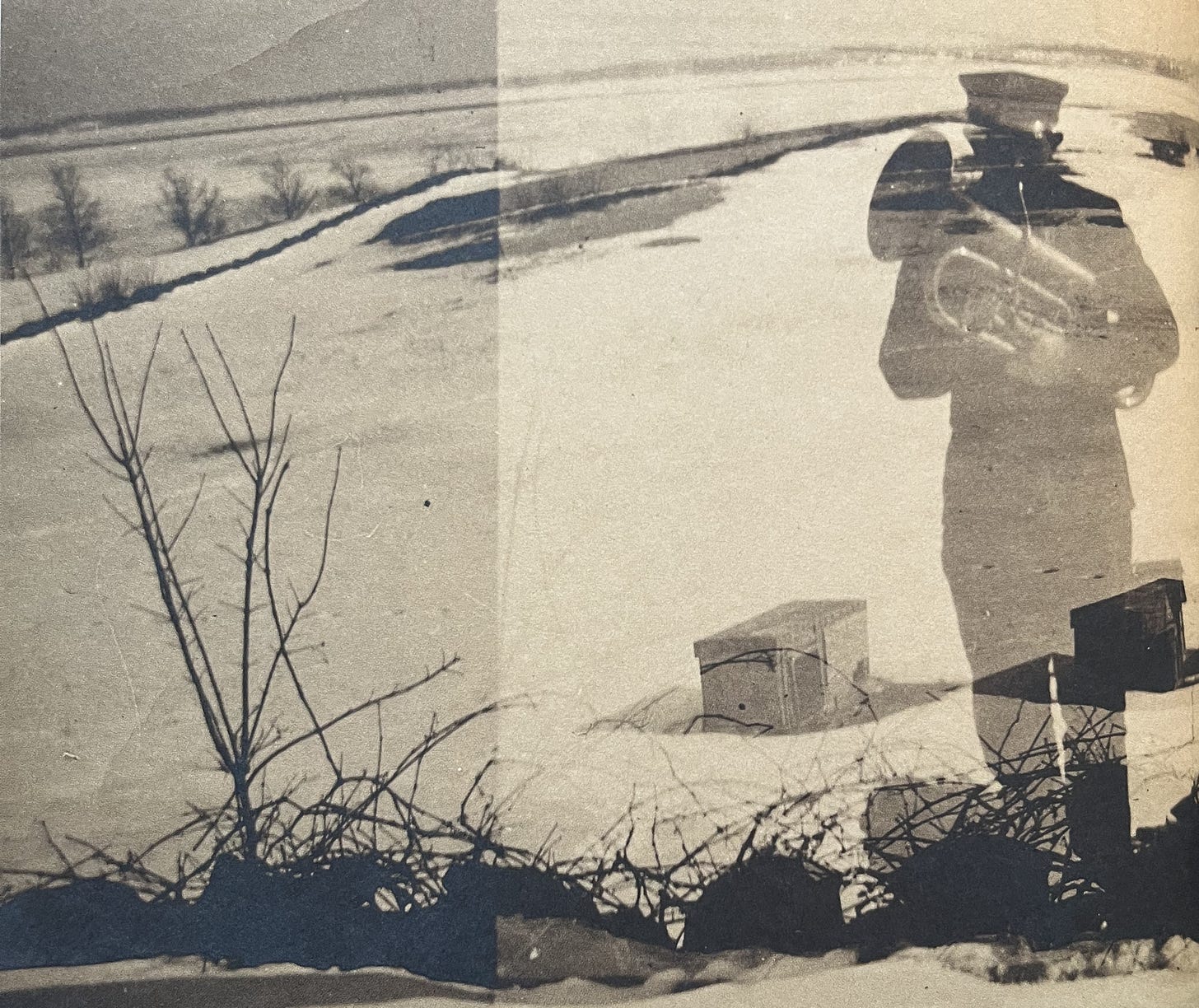

Instead, Roden set out on what became an eight-year journey to find similar musical remnants from the Victorian and Edwardian past, when technology first allowed the average citizen to document through recordings and photographs his or her place in the world, and place in time. The result is “... i listen to the wind,” a singular audio/visual experience that feels like a scratchy, silver-toned portal into a distant world. Combined with two compact discs of found recordings, and brief passages about sound from James Agee, Vladimir Nabokov, William Wordsworth among others, the object is a ghostly meditation on sound — and the absence of it.

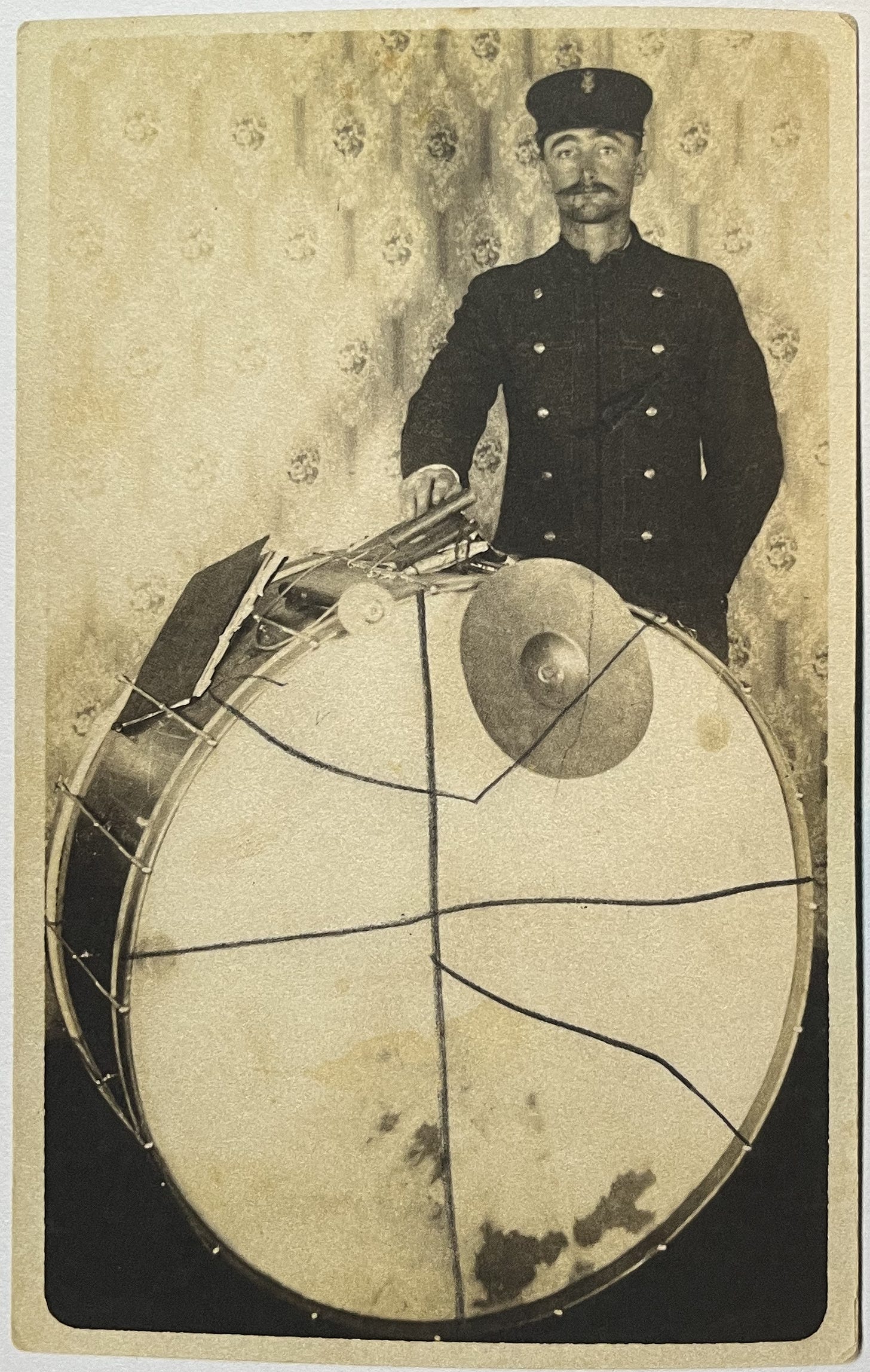

The artist carefully sequenced the pages of black and white photographs — tinted, stained and yellowing — most more than a century old, to create a kind of slide show of anonymous, disappeared souls. A mustached, one-armed, one-man band poses for the camera, a guitar propped on a knee, left foot on a kick drum pedal, the other on a tray of hotel call bells, a bugle and a harmonica wrapped around his neck. Another captures an albino man, a nest of tangled white hair overwhelming his head, playing a violin; a woman stands before a microphone, arms outstretched, lost in song. With each turn of the page, a new apparition arrives from the mystical realm that writer Nick Tosches dubbed as the place “where dead voices gather.”

Roden is well known in the visual and experimental musical art worlds in Los Angeles; last year the Armory Center for the Arts of Pasadena presented a 20-year survey of his work, and a recent installation at Pomona College was his biggest commission to date. Writing of the Armory Center show, Times art critic Christopher Knight described him as “an eccentric virtuoso whose paintings look abstract, but only in the way that a chair, a tree, a face or even a Pop-Tart becomes abstract the longer you look at it — which is to say real, highly specific and not representative of more than itself. His remarkable pictures coagulate.”

The same could be said of “… and I listen to the wind,” which was published by Atlanta-based reissue label/publisher Dust to Digital. The company specializes in issuing antiquated recordings and creating collections of music and photographs, best known among them the landmark 2003 six-CD gospel and spiritual collection, “Goodbye, Babylon,” and “Black Mirror,” an exquisite Ian Nagoski-curated collection of early 20th century music from around world.

“… and I listen to the wind” feels like something altogether different, though, more like a silent movie, a collection crafted from crumbs of the past. Tucked within the simple, minimally designed book’s front and back covers is the music, which Roden organized into a two-volume mix of similarly excavated documents culled from flea market 78 rpm discs.

With no biographical information on the singers provided, each song arrives devoid of context: class, race, ethnicity vanish. One mysterious, anonymous piano and voice ballad, identified only as “societe anonyme,” feels like a lost Kurt Weill miniature. “Graveyard Love,” by Bertha Idaho, recorded in 1928, is followed by Frank Luther’s 1940 version of the haunting ballad “Pretty Polly,” followed by an undated, crackly field recording of birds in an aviary.

The birds and other natural sounds and sound effects punctuate each 60-minute disc with eerie moments of texture: Artificial wind blows from a century ago, a slide whistle mimics a howl; footsteps stomp through squeaky snow.

“I wanted to disrupt this notion that anything can be played on shuffle,” says Roden of the sequencing process. “There’s not a narrative to it, but those are breaths, they’re pauses. They’re moments of contemplation, and they break up the segments of songs — like a sonnet or something. There’s a form to it.”

He did the same when organizing the images to create what he calls “this specifically timed experience. There are these pauses where there are photos with no people, and a quote from a literary text. The whole thing is about slowing down.” And, in an odd way, the visual aspect of the book is also an ode to silence. “There something very absurd about collecting images of something that’s not present in the photograph — which is the sound,” says Roden. “There’s something perverse about that.”